Howard Grimes GETS HIS DAY IN MEMPHIS

- By Alan Richard

- Jul 28, 2021

- 9 min read

Updated: Jul 29, 2021

MEMPHIS - During an event at the Stax Museum of American Soul Music to celebrate his new autobiography, Timekeeper: My Life in Rhythm, Howard Grimes reflected on the book and his incredible career playing drums with Al Green, Ann Peebles, Otis Clay, Syl Johnson and others.

Then The Bo-Keys played a short concert with Grimes behind the drums, at the center of it all.

“It’s so exciting to have our program for our neighbor,” said Stax museum executive director Jeff Kollath, opening the July 21 event. “He is such an instrumental part of the history, not just of this place, not just of Royal Studios… but Memphis music in general.”

Taking Grimes by surprise, Kollath then read a mayoral proclamation declaring July 21, 2021, as Howard Lee Grimes Day in Memphis and Shelby County. The proclamation describes Grimes’ important role in Stax’s transition from country to soul and the impact of his talent and career.

“This is a museum because of the music that was made here, and many hands built it and many hands maintained it, but this right here is a cornerstone,” said Preston Lauterbach, the co-author of Grimes’ book, gesturing to his friend.

After Grimes contributed to an early record by Rufus and Carla Thomas on the Satellite label (soon to become Stax), the Memphis sound took a new, significant turn, Lauterbach said.

“It’s built upon this man’s beat,” he said.

FOR MORE: See our in-depth feature interview with Howard Grimes on his career and his new autobiography. The story was published by the Stax Museum of American Soul Music.

Even before he perfected his groove under Royal Studios producer-bandleader Willie Mitchell, the list of hits on which Grimes played at Stax are really something: Carla Thomas’ “Gee Whiz,” William Bell’s “You Don’t Miss Your Water” (later covered by Otis Redding).

Later, at Royal, came classics by Al Green, Ann Peebles, Otis Clay, Syl Johnson with Mitchell.

“I’m giving myself goosebumps just going through it all,” Lauterbach said.

Like a 'dream'

Grimes’ autobiography is gritty, matter of fact and tells incredible stories about growing up in Memphis, Grimes’ disastrous first marriage and many glimpses into Memphis music throughout the years.

“It’s all written from his perspective, from his voice. He has such a wonderful storytelling voice,” Lauterbach said.

Lauterbach said that Grimes’ playing helped to make the Memphis Sound so distinctive, “that kind of laid-back quality that Willie Mitchell, so beautifully laid back… almost like the beat isn’t going to get there on time.”

In fact, Grimes seems to live by that very rhythm, Lauterbach said.

“That’s his heartbeat. That’s his real self,” Grimes’ co-author said. “There ain’t nobody else like him.”

Grimes thanked so many friends and fans for coming to the event and watching it online.

“It’s been a dream for me,” he said in his soft, low voice.

Then the authors took questions. Someone asked about Grimes’ work with the great but lesser-known soul singer, O.V. Wright. Grimes’ first session with producer and studio engineer Willie Mitchell was on Wright’s 1968 hit, “Eight Men, Four Women.”

“He had so much soul, you could just feel what come out of his voice,” Grimes said.

“Everything came from me through Willie Mitchell. He taught me timing. He taught me how to listen at a song,” Grimes continued. “He said, ‘Howard, I’d like for you to listen at the lyrics.’”

“He said, ‘Lyrics tells the story. People speak of life (in their songs),” he recalled Mitchell saying. “I listened at ‘Eight Men, Four Women,’ and that’s what got things started. So, I owe a great deal to Willie.”

Finding a home

The drummer described how he first connected with Mitchell: Guitarist Teenie Hodges came to the Thunderbird club where Grimes was playing with Flash and the Board of Directors.

Mitchell “had been thru five drummers and he wasn’t satisfied,” Grimes recalled. He committed to try out for Mitchell’s group after a tour as the drummer for Paul Revere and the Raiders.

At the audition, Mitchell urged Grimes to slow down his playing. (See our accompanying feature on Grimes for details.)

“He was so laid back, so relaxed. He was never in a hurry or anything,” Grimes said of Mitchell. “So he taught me how to count time… then put me in charge of setting time.”

After he was hired, Grimes noticed that Mitchell would patch the sound of his drums “in the machine,” or straight through the mikes. Grimes asked Mitchell why he did that with him and not with fellow drummer Al Jackson, best known for his work at Stax with Booker T. and the M.G.’s.

“He said, ‘Well Howard, I don’t want to miss nothing you’re playing,’” Grimes remembered.

“He said, ‘I can hear you coming,’”

“’You play like no other drummer on the planet,’” Mitchell told him.

“And that was a gift for me and that was a blessing, because that’s the reason I’m who I am,” Grimes said.

Grimes also recalled first playing at what would become Stax in 1958.

“Chips Moman took me under his wing… I’d played in clubs from 12 years old. I was too young to be in ‘em, but I was playing them,” he said. “Chips used to always give me thumbs up. This is how I understood, as young as I was, that he accepted me.

“So, you know this is home here to me,” Grimes said of Stax. “When I walked in the door, although it has been revitalized, but it’s similar to the same thing when I first come in. The setting is still… the same, and there was a lot of hits cut in here.”

They cut songs with The Mar-Keys, Prince Conley, Carla Thomas, The Mad Lads and others.

“I just happened to be the kid that Chips looked after,” Grimes said.

He also remembers learning rhythm from his mother—and songs from the radio. “It was almost like she was putting the beat in my ear. I could hear it, that timing,” he said, snapping his fingers.

He remembers hearing Ray Charles’ early records and others. “It moved from that to Bill Doggett, ‘Honky Tonk,’ (the influential 1956 pop and R&B smash), so when I hooked into that… the rest is history,” he said.

Working with the greats

An audience member asked about Grimes’ relationship with Hi Records songwriter Darryl Carter.

“I knew he wrote ‘Woman’s Gotta Have It’ by Bobby Womack (recorded by Moman at American Sound Studio in Memphis), but when he came to Memphis with Willie, it’s where it really happened,” Grimes said.

Carter wrote for Wilson Pickett, Mavis Staples, Otis Clay and many others, and O.V. Wright’s soul-stunner, “Blind, Crippled and Crazy,” Grimes reminded the audience.

When Carter wrote, he “walked the floor singing,” Grimes said. “He never stood still… I picked up everything from the moves… the motion of him singing and walking.”

Together, Grimes and Carter even wrote a gospel song together that just recently was released, he added.

“He’s been a very close friend of mine, as well as Otis Clay,” Grimes said. “They were all my teachers. They were the masters that taught me. I was always taught to think I wasn’t better than anybody else, it was timing.”

“Willie used to always say, ‘Don’t rush. Take your time. And I’m just grateful to Willie, Mr. Able, Floyd Newman” and other mentors, he said.

“When we did Al Green (covering the Bee Gees’ 1960s classic) ‘How Do You Mend a Broken Heart,’ we was trying to get that rhythm. I didn’t know what Willie was looking for. … He said ‘Howard, you gotta make love to your drums,” Grimes said, laughing. “Think about your woman.”

“This is the truth,” he added. “It worked.”

When he played as Mitchell had suggested, “I got light, real light. I got so light on hearing what he was saying. The feel came when I hit the high hat,” grimes recalled. “He said, ‘Now make your left hand look stupid.’

Responding to a question about Isaac Hayes, Grimes recalled having the same homeroom with the future soul-music god at Manassas High. “We had a little combo” and would play at talent shows, Grimes said.

The school’s band director, Mr. Able, sent Hayes to home economics class instead of band. But Hayes found a musical mentor in the home economics teacher, Grimes said.

“He became the genius (he was, in part) because she was a music teacher,” he said. “That’s the reason why he became the master that he was.”

Hayes was a big fan of Brook Benton, Grimes recalled Isaac always was a big fan of deep-voiced crooner Brook Benton (best known for his 1970 smash on Tony Joe White’s “Rainy Night in Georgia”).

Local band leader Ben Branch was hesitant to let Hayes sing at one of their shows, but the club owner at Curry’s Club Tropicana insisted, Grimes said. Hayes sang Benton’s “It’s Just a Matter of Time” and “the whole house came up.”

Hayes wanted to join Grimes and others as a regular musician at Stax, Grimes recalled.

So, Hayes followed Grimes and Floyd Newman over to get a foot in the door, and within a year or so was a staff pianist at Stax, where he’d write and produce Sam and Dave’s hits and later become the man behind the Shaft soundtrack and perfect the soul sounds of the 70s.

Missing ‘Green Onions’

Grimes already was working at Stax when Booker T. and the M.G.’s recorded the classic “Green Onions.”

It could have easily been him on the drums instead of Al Jackson, Grimes said.

The guys at Stax couldn’t reach Howard, so Steve Cropper recommended Al Jackson, Grimes said. “I had heard about Al being with Willie at the Manhattan Club,” he said. “It was almost like we were following each other.”

When Jackson was obligated to play in. town with Mitchell, Grimes said he even filled in with The M.G.’s.

“I went on a five-day tour with Booker T. and them to Detroit. We played behind Jackie Wilson and Chuck Jackson” and others, he said.

“They wouldn’t use no other drummers” at Royal Studios, Grimes added. “I wanted to learn how to play ‘Green Onions’ ‘cause I wanted to learn that beat, so he showed me how to play it.”

Grimes also recalled how he, Mitchell and Hi Rhythm guitarist Teenie Hodges put together the famous “dripping” intro to Ann Peebles’ “I Can’t Stand the Rain.” (See our earlier feature for more on that.)

Mitchell “was an amazing man for ideas. He always just had ‘em swimming in his mind,” Grimes said, reflecting on the sounds in “Rain.”

“It turned out to be one of our biggest records,” he said.

Performance to remember

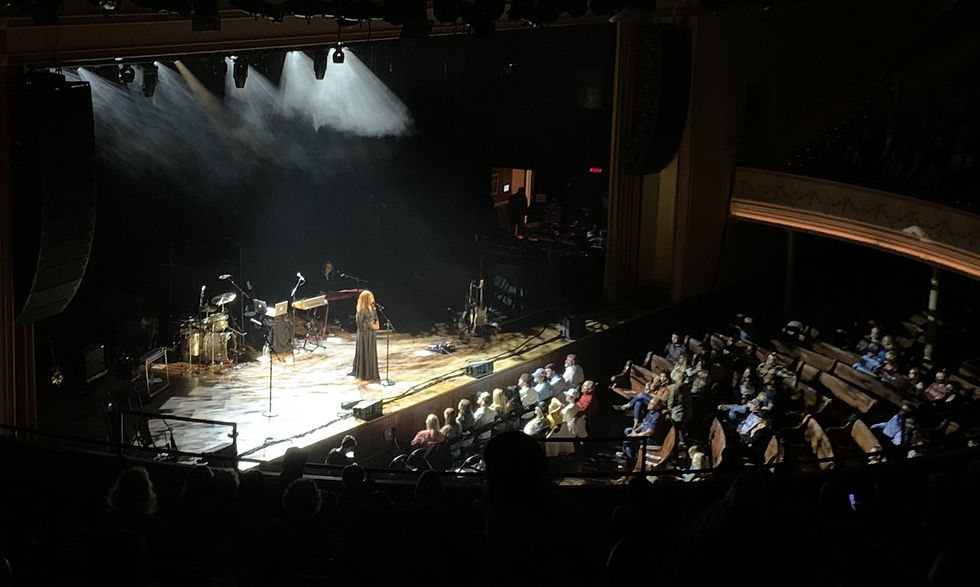

Then Grimes took his seat and set the groove for a special set by The Bo-Keys, a group that brings together older Memphis musicians with some of the city’s special young talents.

The group—led by bassist Scott Bomar, along with Grimes, veteran pianist Archie “Hubbie” Turner (who along with Grimes also played in the Hi Rhythm Section in the 1970s) guitarist Joe Restivo and the incredible Marc Franklin on trumpet and Kirk Smothers on tenor.

Country-soul vocalist Percy Wiggins joined for three numbers before and a bring-down-the-house appearance by the great Don Bryant, whose pleading version of O.V. Wright’s “A Nickel and a Nail”—on which Grimes played drums on the original—was the closest the group got to the Royal Studios sound that master producer Willie Mitchell engineered and that Grimes and the Hi Rhythm Section carried into the stratosphere.

They began with a version of The Crusaders’ “Put It Where You Want It,” which let Bo-Keys guitarist Restivo and the horn section of Franklin and Smothers get to blowing.

“It was a warm-up tune we used to do with the Hi Rhythm Section and Andrew Love,” Grimes said in his introduction. (Restivo’s also in the rock-and-soul combo The City Champs along with drummer George Sluppick and organist Al Gamble.)

After a rendition of Floyd Newman’s 1963 Stax hit, “Frog Stomp”—Grimes played on the original—the band stepped it up on Newman’s “Sassy.” More of a early-rock tune with a steady beat not unlike “Green Onions,” The Bo-Keys’ version featured gave Turner—himself a legend—to shine on organ.

On The Mar-Keys’ “Burnt Biscuits,” another song on which Grimes had played, The Bo-Keys were joined by young harmonica player Damion Pearson, who also performs as Yella P.

Pearson told me after the show that he’s one of the few young people trying to keep country-blues harmonica alive.

The groove goes on

The next tune, Bill Black’s early Hi Records song “Rambler,” epitomized the early Memphis rock-and-soul sound, with a thumping bass and slower, softer groove.

Country-soul singer Percy Wiggins then joined The Bo-Keys for three songs on which he’d sung lead with The Bo-Keys on their records and on tour.

“Give it up for The Bo-Keys. They’re really cookin’, aren’t they?” Wiggins said. “Once again, congratulations, Howard. Give it up for Howard Grimes!”

Then Wiggins pleaded his way through “Writing on the Wall,” “Learned My Lesson in Love” from The Bo-Keys country-influenced album from 2016, Heartaches by the Number, and “Still In Need,” written by Franklin and Wiggins.

“I live uptown in a penthouse suite baby… But baby, oh baby, I’m still in need, yes I am,” Wiggins wailed.

The finale’ saw special guest and former Hi Records songwriter and singer Don Bryant—also known as Mr. Ann Peebles—jump into the room for a bring-the-house-down, screaming version of O.V. Wright’s “A Nickel and A Nail,” the original of which Grimes played on, an early example of Mitchell’s slowed-down groove.

As the song played on, The Bo-Keys gave Bryant room to ad lib and sing the blues. Grimes continued the groove, reminiscent of his perfect pocket on Al Green’s “Love and Happiness.”

Then the museum director, Kollath, bid everyone farewell: “Hope everyone had a great Howard Grimes Day here in Memphis, Tennessee.”

Comments